Life at Low Reynolds Number - Part 2

Introduction.

In Part 1, we discussed how the force needed to push something in water at Reynolds’ number of 1 is 10^-9 Newtons. Who cares for such tiny forces? Bacteria. In the paper, Purcell dives into talking about Bacteria, their flagella and chemotaxis. More importantly for chemical engineers, he talks about diffusion and provides a very nice framework to understand its relevance.

Purcell takes a few side-steps before getting to the point, which is great for us – each of those forays is a fun little paper that leads us into biology. The subject matter is complex enough to be fun to read, and simple enough that terms you don’t understand can be readily googled. And being a physicist, his tone is one of undergraduate-like wonder for a field he’s not done a PhD in. In his own words:

We wander around strictly as amateurs equipped only with some elementary physics, and in the end, it turns out, we improve our understanding of the elementary physics even if we don’t throw much light on the other subjects.

Improving our understanding of elementary physics is very handy for a chemical engineer, because it’s our job to find out how it can be used to ‘throw much light’ on the ‘other subjects’ that Purcell speaks of. Onward.

Flagella: do they wave or rotate?

At one point in time we did not know the answer to this question. But there was a rather cute experiment (described in a short paper) that provided strong support to ‘rotate’.

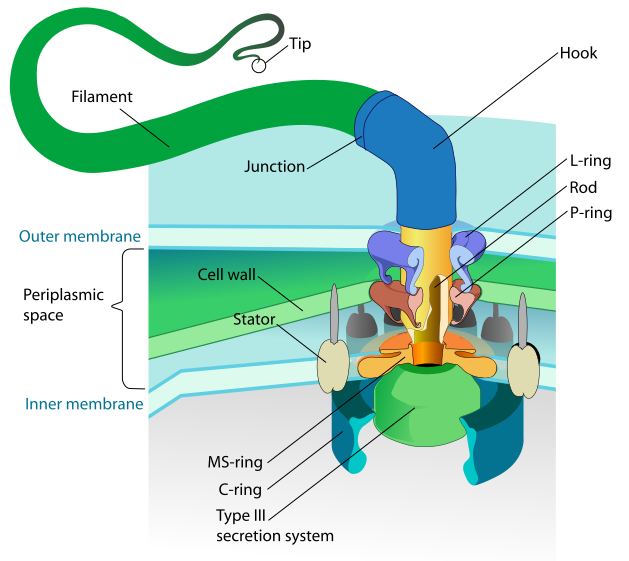

The E. Coli flagella structure looks like this:

There is a particular mutant strain of E. Coli which doesn’t have the filament (green, ending in ‘tip’), and has long hooks (see the blue ‘hook’ above). We’ve also got an antibody that attaches itself to the hook proteins. And it’s polyvalent, i.e. one antibody attaches to multiple hooks, so you can have two cells attached to one antibody, or one cell attached to an antibody which has also attached itself to some debris and thus immobilized itself.

In such cases – the immobilized and tethered cells rotated. This means the hooks (and by extension, the flagella attached to them in non-mutant strains) rotate! We take it for granted now, but must’ve been quite interesting to realize that nature has fitted molecular outboard motors on the posteriors of some cells.

Purcell then goes on detailing the math involved in corkscrew-like or flagellar motion (which I glossed over) and calculates the efficiency of such a motor, which turns out to be all of 1%.

It appears low, but the E. Coli do not care – their total energy needs are minimal. They can usually collect sufficient energy-giving molecules by diffusion, as they move around.

Now we’ve started talking about diffusion. Which means we’ve started talking about mass-transfer. Which means it is time for Part 3!