A Textbook for Process Engineering Job Interviews

Introduction.

After my undergraduate degree, I worked as a process engineer in a company that designed oil refineries. The interview this company put me through was an exciting round of rapid-fire technical questions on distillation tower operation and control, with Each question more complex and thorough than the next. It was fun.

In the months leading up to that interview, the standard textbooks on unit operations and chemical engineering design were not the books that I was reading. While they are essential for an undergrad student, these textbooks do not cover how process equipment behaves during normal operation.

The textbooks I read for my undergraduate courses would have questions of this type:

- How do you design equipment that can work for given operating conditions?

In my interview, I faced questions of this type:

- During normal operation, what are the dynamics that exist within the equipment? What basic principles govern these dynamics?

- What is the response of that equipment/ system to changes in operating conditions? Can it be related to the principles or the dynamics of the equipment?

In other words, my undergrad texts did not talk about process equipment from the perspective of an operator or a troubleshooter. Having this perspective before could be a significant advantage in job interviews, and so here’s a book that provides it.

The Operator Perspective

I’ll reiterate - I want a textbook that discusses:

- How does installed equipment behave under normal operating conditions and what are the dynamics that govern this behaviour?

- How does equipment respond to fluctuations in operating conditions, and what are the principles behind those responses?

Changes in operating conditions may be pressure surges, pump failures, temperature and composition fluctuations, trays in distillation towers breaking and falling off, etc.

“A Working Guide to Process Equipment” does offer that perspective, and it’s an enjoyable read (with bits of irony, irreverence and hilarity sprinkled in). It did help me during my interview. When I was a teaching assistant for the AspenPlus based Process Engineering course, during my MS, I often felt like a few handouts from that book would help the undergrads I was teaching.

Here are some examples:

Distillation Towers

I knew how to approximate number of stages needed for a given separation (the McCabe-Thiele plot), I knew the calculations that went into obtaining NTU/ HTU, I knew how thermodynamics governed separations and other unit operations.

But I was somewhat clueless about the following:

- How does one set distillation column pressure? I.e. where is the valve that governs column pressure? Is there one?

- Partial vs total condensers. How to choose?

- How does increasing reflux affect reboiler duty? Why? How does it affect column diameter?

- Distillation column control. What is it? What degrees of freedom do I have?

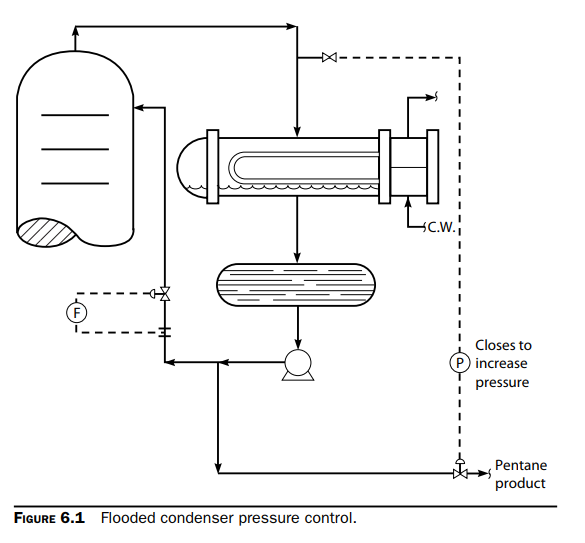

Here’s an excerpt from ‘Chapter 6: Why Control Tower Pressure?‘, along with the associated figure.

Why are distillation towers designed with controls that fix the tower pressure?

Naturally, we do not want to overpressure the tower and pop open the safety relief valve. Alternatively, if the tower pressure gets too low, we could not condense the reflux. Then the liquid level in the reflux drum would fall and the reflux pump would lose suction and cavitate. But assuming that we have plenty of condensing capacity and are operating well below the relief valve set pressure, why do we attempt to fix the tower pressure? Further, how do we know what pressure target to select?

I well remember one pentane-hexane splitter in Toronto. The tower simply could not make a decent split, regardless of the feed or reflux rate selected. The tower-top pressure was swinging between 12 and 20 psig. The flooded condenser pressure control valve, shown in Fig. 6.1, was operating between 5 and 15 percent open, and hence it was responding in a non-linear fashion (most control valves work properly only at 20 to 75 percent open). The problem may be explained as follows. The liquid on the tray deck was at its bubble, or boiling, point. A sudden decrease in the tower pressure caused the liquid to boil violently. The resulting surge in vapor flow promoted jet entrainment, or flooding.

Alternately, the vapor flowing between trays was at its dew point. A sudden increase in tower pressure caused a rapid condensation of this vapor and a loss in vapor velocity through the tray deck holes. The resulting loss in vapor flow caused the tray decks to dump. Either way, erratic tower pressure results in alternating flooding and dumping, and therefore reduced tray efficiency. While gradual swings in pressure are quite acceptable, no tower can be expected to make a decent split with a rapidly fluctuating pressure.

If you find you don’t follow the above paragraph, the earlier chapters in the book set the stage by explaining the terms involved.

Centrifugal Pumps

I’ll leave you with a question from the textbook, from Chapter 34.

Centrifugal pumps are dynamic machines, which means that they convert velocity into feet of head.

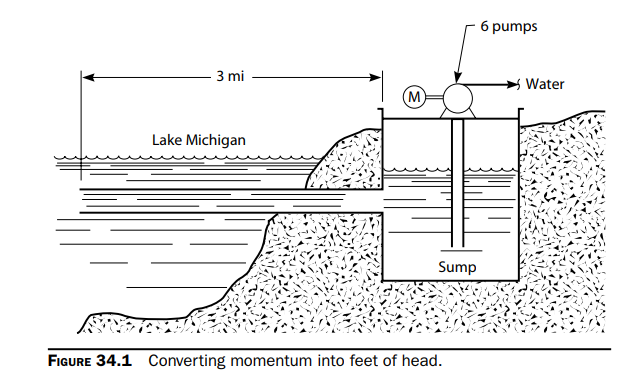

To explain this concept of converting speed or velocity into feet of head, let’s look at Fig. 34.1. This is the water intake section of the Chicago Water Treatment Plant. Water flows from Lake Michigan into a large concrete sump. The top of this sump is well above the level of Lake Michigan. The line feeding the sump extends three miles (3 mi) out into the lake. The long line is needed to draw water into the plant, away from the pollution along the Chicago lakefront. The pipeline diameter is 12 ft. Water flows in this line at a velocity of 8 ft/s. Six pumps, stationed atop the concrete sump, pump water into the water treatment plant holding tanks.

One day, the plant experiences a partial power failure. Three of the six pumps shown in Fig. 34.1 shut down. A few moments later, the manhole covers on top of the sump blow off. Geysers of water spurt out of the manholes. What has happened?

During my interview, the technical questions were more from the perspective of governing dynamics of process equipment as opposed to design from fundamentals. This kind of approach is largely missing from the standard undergraduate chemical engineering texts, so I was pretty happy I came across this one.